In the 1500s, poor and working people earned extra money by knitting – mainly plain sturdy caps, gloves, socks and stockings to sell. With most unable to read or write, written instructions were not needed. Instead, patterns were memorised and recalled through the action of knitting. Special ‘knitting songs’ helped count the number of rounds when knitting with multiple needles. After the day’s chores were done, knitters would sit together and sing as they made their caps, gloves, socks and stockings.

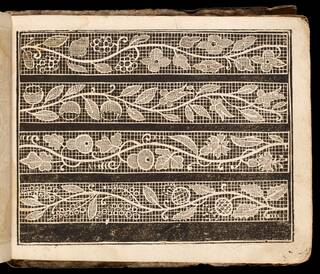

More decorative knitting might have been inspired by patterns books published in the 1500s and 1600s for a variety of arts, such as embroidery. These offered simple designs on a grid, which translated easily to knitting, using different colours or alternating different stitches.

With graph paper, anyone could draw out their own design and work it into some knitting, such as this pincushion from the 1700s.

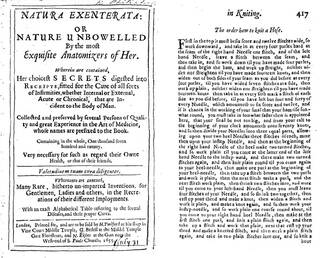

The first knitting pattern published in English appeared in a book with the unusual title, Natura Exenterated or Nature Unbowelled by the most Exquisite Anatomizers of Her (1655). Knitting historians have attempted to knit the book’s pattern ‘The order how to knit a Hose’ and succeeded – sort of. The instructions form one long sentence, with a variety of words used for ‘knit’ and ‘purl’, no directions for needle size, yarn weight or tension, but . . . it was a start and it showed how difficult it was to explain the technique using only words.

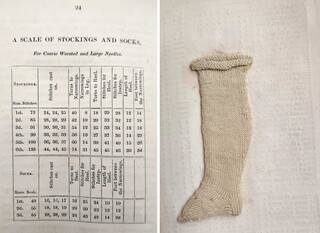

Instructions on Needlework and Knitting was published in 1832 for schools teaching poor children how to knit and sew. It included directions for knitting socks in several sizes, as well as providing a miniature sample.

The Workwoman’s Guide, first published in 1838, offered guidance on the economical making of clothing and domestic furnishings. It included a chapter on knitting, with patterns for practical items such as socks in a variety of sizes, boots, caps, mittens for babies and adults, blankets, purses, shawls and undershirts. The Workwoman advised on yarns and knitting needles, and gave instructions for casting on and off (how to start and finish a piece of knitting), and a variety of fancy stitches. The latter were for the pattern of the motif only – sometimes an odd or even numbers of stitches, or a set number, such as four or eleven stitches – which knitters adapted to whatever garment they were knitting. The instructions for ‘The Rough Cast, or Huckaback Stitch’, we know these days as moss stitch:

Set on any uneven number of stitches.

Knit plain and turn stitch alternately, observing to begin every row with the plain stitch.

This is very pretty, and firm, and suitable for borders.

While we might recognise the reference to ‘knit’ or ‘plain’ stitch, ‘back-stitching’ ‘pearling’ or ‘turn stitch’ all refer to what we know today as purl.

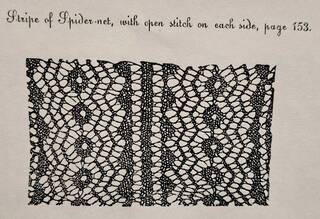

The next book to include knitting patterns was Jane Gaugain’s The Lady’s Assistant, in 1840. Gaugain devised a very complicated system of symbols for knitting stitches with inverted alphabetical letters, but not all knitting books used them. Authors recognised the need to show readers what the patterns looked like, using the illustration techniques available in the 1800s.

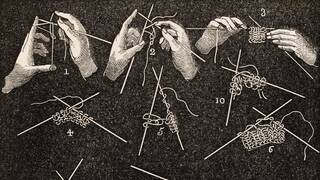

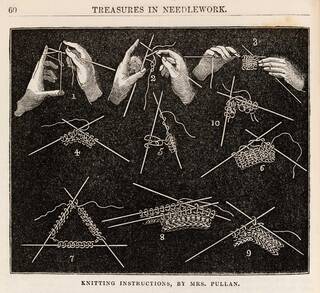

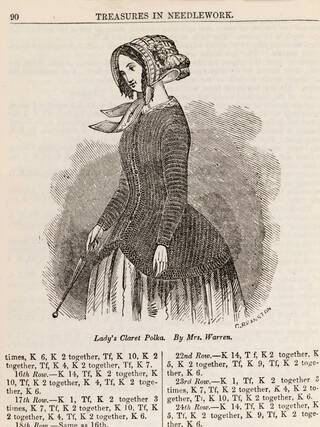

Gaugain included illustrations of the finished pieces, whilst the authors of Treasures in Needlework (1855) included diagrams showing how to hold the needles and yarn.

By the mid-1800s, literate middle-class and ‘gentle’ women had taken up knitting as a hobby to make useful and decorative items. Frances Lambert, Cornelia Mee, Miss Watts and others published many books of knitting patterns during this century. These included practical knitted accessories, such as gloves, hats, mittens, socks and stockings, as well as decorative items like ‘muffatees’ for the wrists, decorative fringes, lace-knitted shawls and beaded knitting. Mrs. Godfrey John Baynes published The young mother's scrap book of useful and ornamental knitting for the nursery (1848). And The floral knitting book, or, the art of knitting imitations of natural flowers (1847) offered patterns for eleven flowers, including convolvulus, narcissus and snow drops.

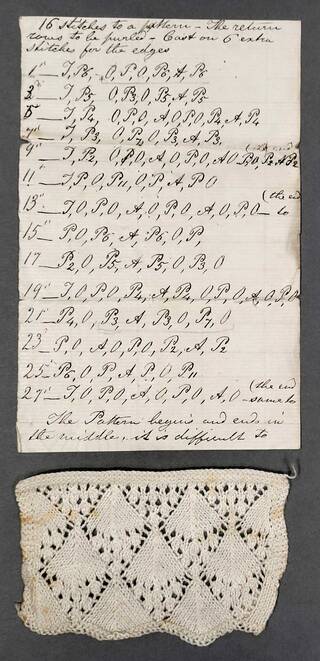

Women’s magazines, such as The Magazine of Domestic Economy (1836 – 42), and The Queen, the Lady's Newspaper (1863 – 1926), regularly featured instructions for a variety of accessories, garments and furnishings to sew and embroider, as well as knitting patterns. In addition to published patterns, knitters wrote down their favourite stitches and instructions for useful accessories to share with family members and friends. These rarely survive, but the V&A’s Archive of Art and Design has a collection of 70 knitting patterns dating from about 1850 to the 1860s. Some are pieces of paper with the repeat of a fancy pattern written out and a small, knitted sample attached, so that someone trying the pattern could check that they had got it right.

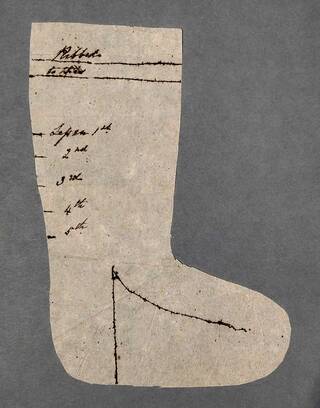

There are also patterns for a baby’s shoe, a fashionable jacket called a ‘polka’, a pen wiper and sock outlines in three sizes, with the places to start decreasing, increasing and shaping the heel marked. You could knit the sock with any size needle and yarn, and rather than counting rows and stitches, you just measured your knitting against the outline and shaped it accordingly.

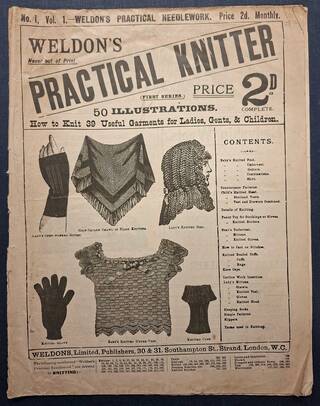

Weldons published the magazine Practical Needlework (1888 – 1959) with issues dedicated to knitting patterns. In 1906, they introduced simple abbreviations for knitting stitches for their patterns that became the standard. The companies that manufactured knitting yarns began issuing patterns using their own materials. They employed designers to invent practical and fashionable accessories and to write the patterns, which were published as leaflets. Accompanied with a photograph of the knitted garment, these sold for a few pennies in shops selling the manufacturer’s yarn and could also be purchased by post.

In 1908, the yarn company J&J Baldwin hired Marjory Tillotson (1886 – 1965) to write patterns for knitted accessories for the ‘Beehive’ series, although her name never appeared on the leaflets. When Baldwin merged with J Paton in 1920, Tillotson continued her patterns for Patons & Baldwin’s leaflets, as well as publishing books on knitting with more detailed instructions for mastering techniques.

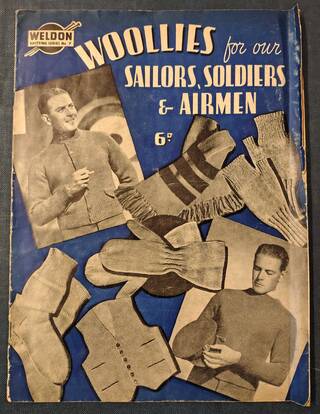

During the First and Second World Wars, knitting became a national duty, to provide warm accessories for air force, army and naval personnel, and a way for worried relatives to contribute to the war effort. Magazines, yarn companies and the UK government issued patterns for sturdy balaclavas, gloves, hats, scarves, socks and undershirts.

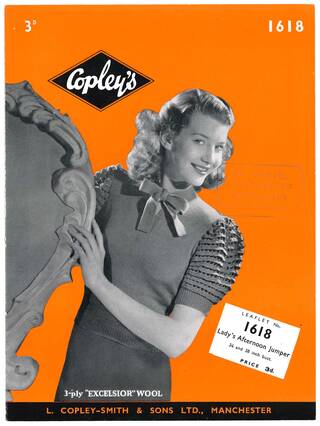

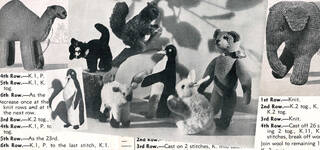

Patterns for knitted baby clothes, children’s jumpers and stuffed toys remained favourites. Fashionable women’s garments were always in demand, from the polka jacket of the 1860s through to knitted dresses in the 1910s and stylish jumpers in a huge variety of designs in the 1940s and 1950s.

The yarn manufacturers Copleys, Lister, Patons & Baldwins, Scotch Wool, Sirdar and others continued to offer knitting patterns. Publishers such as Bestway produced these along with patterns for other handicrafts. Needlework and Stitchcraft issued many knitting patterns and Woolcraft was a magazine dedicated to knitting and crochet.

James Norbury (1904 – 72) was an important British hand-knitting designer who started at Copleys and went on to become head designer for Patons and Baldwins in 1946 where he remained until 1969. He mastered the new medium of television, presenting knitting programmes for the BBC in the 1950s and 60s, as well as publishing many books.

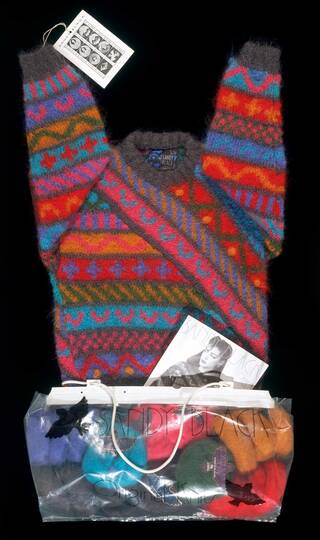

The fashion magazine, Vogue, produced sewing and knitting patterns for readers to make the latest, most stylish clothes at home. Designers devoted to knitting, including Sandy Black, Kaffe Fassett, Sasha Kagan, Patricia Roberts and Edina Ronay, revived the interest in handknitting in the 1970s and 1980s. As well as producing high fashion handknit garments, these designers also published patterns for their creations, sometimes providing needles, the yarn of the right texture, weight and colour as part of a kit, to ensure the desired result.

Shetland lace knitting had been very popular in the Victorian era and as early as 1847 there was a book specialising in lace knitting: The Lace Knitter’s Intelligible Guide, by Mrs Banks. When Edward, the future Duke of Windsor, wore a Fair Isle jumper at a golfing tournament in 1922, he started a fashion for this Shetland-style of handknitting. Knitters began seeking out other regional styles in the UK, such as Guernsey/Jersey jumpers, Argyll and Aran patterns, and books reviving these styles appeared in the 1970s and 1980s. Interest spread to unique knitting styles outside the UK, including Scandinavian and Mediterranean countries.

The arrival of the internet transformed knitting patterns and instructions. A wealth of patterns — new and old — became available online with YouTube also featuring video tutorials ranging from instructing beginners how to knit, to demonstrating complicated stitches and intricate designs. The digital revolution has taken us full circle, back to watching and doing — almost! Unlike the communal teaching and practice of knitting, a YouTube tutorial can’t see what you’re doing wrong and correct you, although with the advent of AI, who knows?