Take this traditional 1950s Wedgwood cup and saucer, which forms part of the 175,000 objects and archives at the V&A Wedgwood Collection in Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent. For many, its aesthetic and function will be of immediate interest. However, objects can also be threads in the tapestry of someone’s life.

Through research conducted at the V&A Wedgwood Collection, the Royal College of Art and the Wiener Holocaust Library, this everyday object acts as a prism for two interlinked stories. One story reveals the compassion and empathy of the Wedgwood family, who set out to assist those being persecuted across Central Europe during the 1930s. The other highlights the bravery, determination and talent of a young refugee called Ulla Goodman (1924 – 81), who was helped by the Wedgwood family, and became an important designer at the company during the 1950s.

These intertwined stories serve as a timely reminder of the thousands of refugee artists displaced during the 1930s, the help they received, their assimilation into a new society, and how they contributed to British industry, arts and culture.

The Wedgwood story

We start with the Wedgwood family. Specifically, the descendants of the Staffordshire potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood (1730 – 95), who, in 1759, founded his ceramics company which achieved global success and remains in production today.

While the Wedgwood name is synonymous with ceramics, it is also connected to compassion and social activism. Probably the most famous example is the manufacture of the anti-slavery medallion by Josiah Wedgwood in 1789. The wearable medallion, featuring a Black man kneeling in chains, with the embossed phrase ‘Am I not a man and a brother’ became a key emblem in the campaign to end the transatlantic slave trade. This humanitarian spirit can also be seen among his descendants, who embraced a determination to help thousands of European refugees struggling to find sanctuary in 1930s Britain.

Britain and refugees

The British Government’s initial response to the refugee crisis was haphazard, recognising the persecution in Germany, but reluctant to provide sanctuary to those who might challenge the British workforce for employment. This hesitancy was worsened by British immigration policy, as there was no legal concept of right to asylum. Although Home Office officials had the power to permit political refugees or those escaping discrimination, eligibility was determined by their opinion of the individual in need.

This changed in 1938 in response to Kristallnacht, an escalation of persecution in Nazi Germany. Additional categories of people were granted temporary asylum, such as unaccompanied children under 17 and adults willing to become domestic servants. However, securing refuge remained difficult, with unaccompanied children needing a financial guarantee from a guarantor in Britain. This led many European families to post advertisements asking for British residents to sponsor their child. The safety and treatment of refugees was almost solely dependent on the compassion of others.

Josiah IV

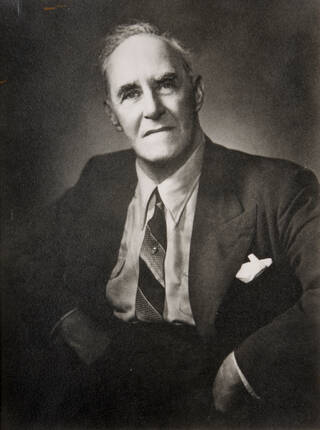

The fifth and sixth generations of the Wedgwood family, Colonel Josiah Wedgwood MP (1872 – 1943) and his son Josiah Wedgwood V (1899 – 1968), were amongst those who helped refugees.

By the 1930s, Colonel Wedgwood was a well known public figure. He was a veteran soldier, having served in the Boer War (1899 – 1902) and the First World War (1914 – 18). He also boasted a political career, elected Liberal MP for Newcastle-under-Lyme in the 1906 General Election and transferring to the Labour Party in 1918. He earned a radical reputation; never afraid to speak out on controversial topics, including Indian Independence and the appeasement policy toward Nazi Germany. His primary belief was in the protection and advocacy of human rights, or as he described a ‘hatred of cruelty, injustice and snobbery, and an undying love of freedom’.

As Nazi persecution escalated during the 1930s, the altruistic Colonel’s attention turned to the plight of refugees in Central Europe. In the House of Commons, he frequently advocated for the reform of British policy regarding immigration and asylum by citing firsthand accounts of persecution. But emotive speeches were only a part of the Colonel’s efforts, with his main contribution becoming a personal sponsor for numerous refugees. He invited them to stay at the aptly named, The Ark, his bungalow in Moddershall Oaks, Staffordshire. It was fitted with beds, blankets, and cookers to ensure its suitability. Residents would settle until work was found or until they could migrate.

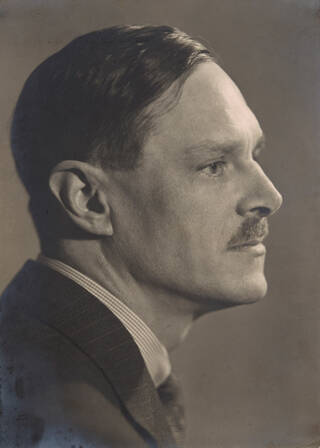

Josiah V

While managing his bungalow refuge, the Colonel’s son and namesake, Josiah V, also assisted in the rescue effort. Josiah was propelled by a similar compassion: in a 1945 essay titled Has Hitler conquered our minds?, he argued that true victory would only be achieved through the following principles:

That charity, irrespective of race remains the highest virtue; that hatred remains a vice except when it is the impersonal hatred of cruelty and injustice; that justice does not punish for the mere fact of being born on the wrong side of a frontier or of speaking the wrong language; and that in the long run, European civilisation can only be reborn by the fraternisation of all its peoples.

Becoming Managing Director of Wedgwood in 1930, Josiah V was tasked with stabilising the company during a tough economic downturn, resulting in designs such as ‘Veronese’ ware, shaped and decorated in simple forms and colours to be produced and sold at reasonable prices. Despite this priority, he made efforts to support European refugees who had already settled in Britain, mainly through helping them find employment. This included work at the Wedgwood factory, disclosing in 1939 that he had ‘made arrangements for another two refugees to come as trainees in September’.

This father and son pairing would ultimately result in 222 refugees finding safety. Within this group was a 14-year-old German Jewish refugee called Ulla, and it’s here where the two stories associated with the cup and saucer begin to intertwine.

Ulla Goodman

Born in Berlin on 8 December 1924 to Eva and Kurt Weinmann, Ulla arrived in England on 26 July 1939. Her £50 sponsorship was funded by Colonel Wedgwood, who came to assist through an incredibly fortuitous chain of events.

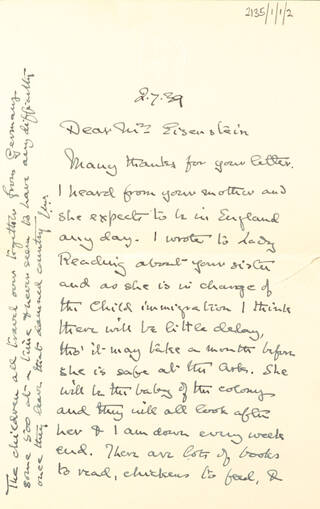

In 1936, Ulla’s half-sister Ursel had migrated to South Africa with her husband. Here, she met another Jewish refugee called Paul Oppenheim, who was married to Gloria Wedgwood, Colonel Wedgwood’s youngest daughter. This connection likely saved Ulla’s life, with Ursel writing to the Colonel in the summer of 1939, wishing for her sister to become a guest at The Ark. Without hesitation, he agreed to help, adding a comforting declaration that Ulla “will be the baby of the colony, and they will all look after her…. there are lots of books to read, chickens to feed and a bicycle to ride”.

Despite the good news, Ulla was nervous about the journey to The Ark. Like thousands of other refugees, sanctuary came at the cost of leaving friends and family, as well as uncertainty about the future. In a 1939 postcard sent to her sister Ursel, she explains these feelings, “My friend and I are going to London today, and I was just so sad that I should be left alone. I am very happy for Mum, because now there is much more possibility that she can come to you”.

Unfortunately, Ulla’s mother, Eva, never left Germany, and the pair were only able to keep in touch through fleeting Red Cross correspondence. In early 1942, Ulla wrote, “Another birthday passed, and I wish with all my heart it is the very last we have to celebrate apart”. Her mother replied affectionately, “Beloved child, Thousand thanks for your lovely congratulation. I am healthy and I am working. Write without delay about your own wellbeing. In love and kisses, Mum”. In November of the same year, Eva was murdered at Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

With her father Kurt passing away in 1934, and her half-sister in South Africa, the 14-year-old was now truly alone. She maintained a drive and determination to start a new life in Britain by following her passion for art.

In June 1941, thanks to help from Colonel Wedgwood, Ulla joined Wedgwood to work as a ‘handpaintress’ at the factory in Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent. She left in 1942, and began lodging in Derby, where she found a job painting and decorating at Crown Derby Porcelain Company. That same year, Ulla also began a full time four-year course at Derby School of Art. By 1946, she had gained a Ministry of Education certificate in Drawing and mentioned to a friend that several teachers were ‘interested in her’ and had advised her to apply for a scholarship.

As well as carving a career for herself, Ulla also fell in love. In 1947 she married Wilfred Goodman, a fellow student at Derby School of Art. Sadly, for reasons unknown, the marriage to Wilfred was short-lived and compelled her to relocate to London. Facing another upheaval, Ulla asked the British Jewish Refugee Committee for assistance and was awarded £120 to complete a two year part-time course at Wimbledon Art School. Here, she achieved further qualifications in pottery and terracotta.

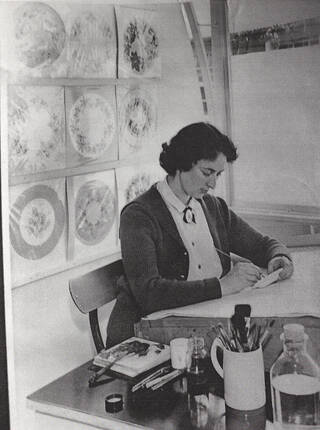

Then, in 1949, she successfully applied to the prestigious Royal College of Art (RCA). In her application form, the Principal of Wimbledon Art School provided Ulla a glowing reference, stating that she was ‘a good student, unusually resourceful and a hard worker’ who would be ‘a very suitable candidate who could profit greatly from a course at the RCA’. Ulla lived up to these words, graduating in 1953 with a degree in Ceramics. Now a graduate, Ulla began her search for a job. Fortunately, Josiah Wedgwood V, just like his father, appeared at the most opportune time.

In 1953, Ulla mentioned in a letter to her sister that the Wedgwood company "want me to sign an agreement in January, when Josiah Wedgwood [V] comes to the College". She accepted the offer and was employed as a full-time designer, working under Art Director Victor Skellern (1909 – 66). At this time, the company was developing its post-war design strategy, which included new patterns, shapes, and glazes, and Ulla produced designs to meet this new company vision.

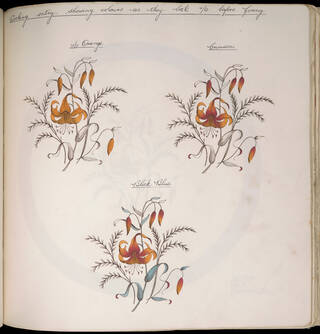

She created various designs depicting floral motifs. While most saw moderate popularity, one pattern named Tiger Lily, became a huge success for the company. It is this design which adorns the 1950s Wedgwood cup and saucer.

Samples of Tiger Lily were first displayed at the 1956 Wedgwood Design Parade held at the Wedgwood New York Office. Victor Skellern recorded visitor reactions for the company and observed that, "it was interesting to note the favourable reaction in particular to Tiger Lily". Skellern also highlighted that Tiger Lily was placed second best in a visitor ballot, and a representative from popular retailer Gumps, in San Francisco, had bluntly commented that they would "take that if you could stock it".

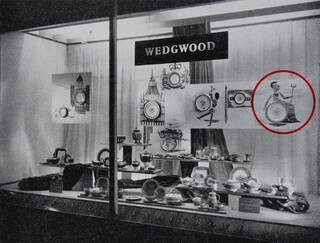

In Britain, Ulla’s pattern saw similar success, being recorded in the 'Best Seller' data kept by the Company from 1956 to 1961. Given this popularity, unsurprisingly, the pattern became a figurehead in Wedgwood Marketing. In 1958, a Tiger Lily plate was used as the ‘Shield of Britannia’ for a showroom window advertisement in Oxford Street, London. In hindsight, the use of a refugee’s artwork in the personification of British strength and identity is a powerful image.

The design was only discontinued in 1965, after a run of nine years.

Despite Ulla’s success at Wedgwood, by 1960, she had left the company. Remarkably, she dedicated the remainder of her life to the transcendental meditation movement, moving to India to contribute as a teacher. During this period, Ulla wrote to a family friend, where she contemplated her displacement and yearned for a permanent place to call home.

It happens from time to time that my life suddenly gets gathered up, as it were cast into the melting pot of destiny. And this will always happen to me when I least expect it; when I settle down somewhat complacently, fancying that my life is taking a certain recognisable shape which allows one to predict the sort of course it will take in the future. Just then – “swoop” – it is all gathered up by some supernatural power, cast into the cauldron of destiny and I just stand aghast wondering in what shape my life will be recast next.

In the late 1960s, she returned to Germany, establishing a meditation centre in Lower Saxony. She passed away in 1981, aged 57.

The stories ingrained in this cup and saucer not only convey the importance of kindness and compassion, but also the valuable contributions refugee artists, such as Ulla, have made to Britain. In the poignant words of one refugee who fled to Britain during the 1930s, “They have opened the doors for me, but I have enriched them”.

Explore more stories from our Wedgwood Collection.

Plan a visit and discover what's on at the V&A Wedgwood Collection, Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent.