The case has since been examined closely, highlighting the injustice of the trial and the underlying prejudices shown toward Pratt and Smith by all classes of society. Attention has also been drawn to those who pleaded for the pair to be pardoned. Unexpectedly, one plea for pardon came from the magistrate who had committed the men to trial – Hensleigh Wedgwood (1803 – 91), grandson of Staffordshire potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood I (1730 – 95). His letter to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell (1792 – 1878), has since been considered ‘the bravest in a contemporary sodomy case’ (Chris Bryant, James and John: A True Story of Prejudice and Murder, 2025).

Exploring Wedgwood’s protest reveals a deeply religious but conflicted figure who attempted to save the lives of Pratt and Smith. The content of his plea and the injustice of the trial serve as a reminder of the long fight for LGBT+ rights in Britain, which continues today.

‘The love that dare not speak'

The harshness of the sentences imposed on Pratt and Smith occurred in a paradoxical time of mass reform in Britain. Only a few years before, the nation had seen the passing of the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. Yet, the celebrated authors behind these acts were at best indifferent or at worst supportive of laws which suppressed others, particularly the working classes.

Such suppression was the result of a country in the midst of a moral panic, with rising concerns of moral decay associated with rapid urbanisation and industrialisation. The Church of England warned its followers of eternal damnation if they did not offer repentance and conformity. Even the head of state, King George III (1738 – 1820), was persuaded to issue the Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue a few decades earlier. He urged his subjects to suppress sinful behaviours such as vagrancy, drinking, swearing and debauchery, and instead return to a life of devotion and integrity.

Same-sex relationships were the perceived zeniths among the declared vices. Clergy, judges, politicians and other authorities had long denounced homosexuality as an offence against God’s will, which should – and did – attract the sternest punishments. It was a felony punishable by death and dispossession under the Buggery Act of 1533, which declared the act as ‘detestable and abominable’. In comparison, the standard punishment for the lesser offense of ‘attempted buggery’ was the pillory where public mobs were free to assault prisoners.

Newspapers, publications and satirical material served to disseminate and reinforce this abhorrence. Journalists often made no attempt to distinguish between cases of homosexuality and those charged with assaulting an animal. Some made sensationalist claims – a reporter for an 1806 edition of the Staffordshire Advertiser asserted that violent condemned prisoners would be ‘ashamed of being hung’ alongside men with ‘unnatural’ sexual orientations. Even mentioning the felony was deemed too scandalous. Instead, editors and printmakers used demeaning labels to address those accused, such as ‘Ganymede’. The term refers to Greek mythology, where the god Zeus fell in love with the beautiful male youth Ganymede. Taking the form of an eagle, Zeus carried him to Mount Olympus, where he became a lover to the god.

This widespread bigotry meant that anyone charged with these offences were unlikely to be subject to a fair trial – there was a presumption of guilt, not innocence. Pratt and Smith’s case serves as a horrifying example.

The trial

On Saturday 29 August 1835, James Pratt and John Smith met at 45 George Street, a run-down lodging house off Blackfriars Road in Southwark, London. Pratt had been a servant, a smith (metalworker) and a labourer, he was married with a daughter. Smith was single and supported his mother. Both were poor and out of work.

During their stay, the landlord and his wife allegedly witnessed the pair having sexual relations and reported them to the local authorities. Pratt and Smith were arrested and sent to the Union Hall Police Office, Southwark. Duty magistrate on that day was 32-year-old Hensleigh Wedgwood (1803 – 91). Despite his position, Wedgwood had limited authority on the matter. Since there was ‘sufficient’ evidence the crime had been committed, he had no option other than sending the pair for trial.

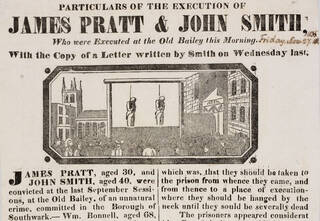

The trial was held at the Old Bailey on the 21 September 1835, where the two men were convicted and sentenced to death. At the trial, they were not guaranteed a defence lawyer, who incidentally would not have been allowed to address the jury. Therefore, no attempt at highlighting the invasion of the pair’s privacy was made, nor any challenge to the implication that their relationship endangered society. All the men could do was recite their original ‘not guilty’ pleas.

Close examination of the trial reveals a place more akin to a vulgar spectacle than a court of law. It was overseen by Judge Sir John Gurney (1768 – 1845) and Recorder of London, Charles Law (1782 – 1850) who were both devout Christians. Judge Gurney saw the crimes as evidence of men being ‘seduced by the instigation of the devil’. Meanwhile, Law, upon delivering each sentence, demanded that James and John be isolated from the other prisoners, as the latter group ‘would have been contaminated’ by their presence. Reportedly, Pratt and Smith ‘wept very much’ during Law’s sentencing. Further misery was inflicted on the pair as they were committed to London’s disease-ridden and overcrowded Newgate Prison to await their executions. On the Sunday before a hanging, condemned prisoners at the prison would visit the chapel and sit around an empty coffin to listen to their last sermon.

There was the possibility that their executions could be commuted (reduced in severity). Capital sentences were officially reviewed and sanctioned by the ‘Grand Cabinet’, which in 1835 would have included King William IV (1765 – 1837), Recorder of London Charles Law (who had overseen the trial), and Home Secretary Lord John Russell. Each review would include any petitions for mercy.

There was a public petition organised by Pratt's wife, Elizabeth (d. 1873), who collected 55 signatures. When Law delivered his report on the case, it included a letter from Hensleigh Wedgwood ‘in favour of the Prisoners’. However, he made no mention of Elizabeth Pratt’s petition.

Seventeen individuals had their cases reviewed by the Grand Cabinet and all had their death sentences commuted, except for Pratt and Smith. They were executed by hanging outside Newgate Prison on the morning of 27 November 1835.

Hensleigh’s plea

Pratt and Smith’s fate highlights a system and society which saw their sexuality and class as criminal. Despite this, elements relating to the case can be praised. Specifically, those who pushed back against the moral outrage, trivialising the punishment to save the lives of the pair. This includes magistrate Hensleigh Wedgwood.

Wedgwood was the youngest son of Josiah Wedgwood II (1769 – 1843) and grandson of Josiah Wedgwood I. He was born at Gunville House, Dorset and later enrolled at Cambridge, graduating from Christ's College in 1824. Between 1829 – 30, he was a fellow of Christ's College and read for the chancery bar (trained to become a barrister), which he qualified for but never practised. He was appointed police magistrate at Union Hall, Lambeth in 1832. In the same year he married Frances ‘Fanny’ Mackintosh (1800 – 89), daughter of prominent liberal politician Sir James Mackintosh (1765 – 1832). Together they had six children, including philosopher, writer, and feminist Frances ‘Snow’ Wedgwood (1833 – 1913).

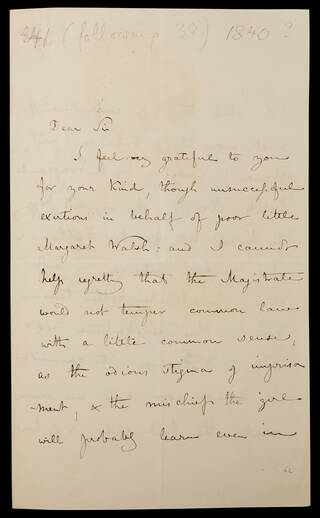

On the 6 October 1835, Wedgwood sent a long and decisive letter to Home Secretary Russell, where he made the following statements:

I feel so strongly that death is not the punishment for their offence and the dreadful situation they are in shocks me so much that I cannot neglect a chance of saving them…

…Their offence I allow is a very heavy one against God, and shows a most degraded nature, but surely, mylord, it is not a crime against society of such a description as to call for the spilling of blood….

…I am convinced that the only reason why the punishment of death has been retained in this case, is the difficulty of finding any one hardy enough to undertake what might be represented as the defence of such a crime…

…there is a shocking inequality in this law in its operation upon the rich and poor. It is the only crime where there is no injury done to any individual and in consequence it requires a very small expense to commit it in so private a matter…It is also the only capital crime that is committed by rich men but owing to the circumstances I have mentioned they are never convicted.

Not overlooking his use of abhorrent language to reference Pratt and Smith, each of Wedgwood’s statements are powerful. In his eyes, the punishment was excessive, the crime too stigmatised for a fair trial, the relationship not injurious to society, and the law prejudiced against the poor. Similar arguments had been made before, but only anonymously. Wedgwood was happy to sign his name on the letter, which may have been seen as blasphemous. He risked his job and reputation, so why did he send it?

Faith, conscience and compassion

Father sympathised with his strong enthusiasm for liberty, truth and humanity.

Ironically, faith played a part in his decision. Wedgwood followed the popular Christian evangelical movement, where he would have been educated in the importance of puritanical morality, conversion and social action. He and his family lived in Clapham, South London, an area which was home to a concentration of Evangelicals referred to as the ‘Clapham Sect’. Prominent from 1790 to 1830, the Sect was based at the Holy Trinity Church in Clapham Common and famously campaigned for the abolition of slavery under the leadership of William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833). However, Wilberforce also advocated for the morality crackdown in Britain, and was influential in persuading King George III to make his proclamation in 1787. Believing in Wilberforce’s austere society may explain Wedgwood’s repeated use of the term ‘degraded’. Yet, in contrast to his peers, to him this belief did not determine the value of an individual. Wedgwood’s connection with radical Scottish minister Rev. Alexander John Scott (1805 – 66) could explain why.

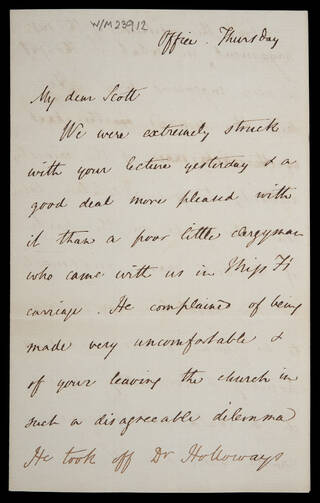

Scott was an influential non-conformist preacher, who did not believe in the Church of England’s view that humans hold a sinful nature, and that salvation only occurs through redemption. Alternatively, he taught universal atonement – all people are created equal before God and are guided by the God-given faculty of conscience. Any attempt to limit the love of God was ‘negation of the Gospel’. Correspondence held at the V&A Wedgwood Collection illustrates Wedgwood’s sympathies with Scott’s implication of equality. In about 1836, he wrote to Scott describing his happiness that, "I always find that intercourse with you draws me closer to God". A year later, he reflected on one of Scott’s lectures writing, "you hold a doctrine that I should very much like to hold…that every event that happens to everybody is contrived by providence as to be the best for him that could have happened".

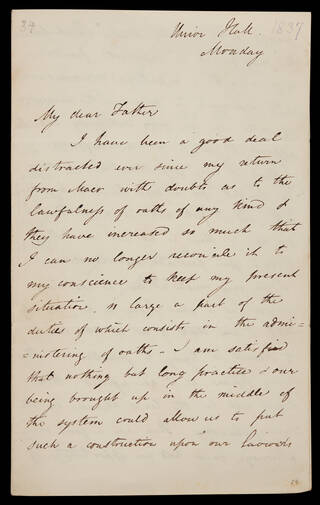

Wedgwood aligned belief with action. He was obsessed with the idea of maintaining a good conscience, acting in what he believed to be in accordance with God. It was why he resigned from the role of magistrate in 1837, despite a generous salary and objections from family and friends. He had progressively become convinced that swearing oaths inferred a lack of honesty amongst Christians. When informing his father, Josiah II, he wrote, "I feel that it is not lawful for me, and there is no use in letting [£]800 a year persuade one's conscience". Only Rev. Scott praised the decision, congratulating Wedgwood for "acting from mere conscience…at a time it is by many considered to be an impossible motive".

A strong compassionate trait, apparent in his correspondence and actions as magistrate, may also have led to his decision to help Pratt and Smith. In October 1837, Wedgwood oversaw a case involving 30-year-old Ann Grant. She was charged with vagrancy after being found ‘wandering the streets’. Wedgwood asked that parish authorities should relieve her, and grant money to purchase food. Reportedly ‘the poor creature, having thanked the worthy magistrate for his humanity, left the office’. Wedgwood reviewed a similar case of vagrancy in June 1837 involving Rev. John Norman, who was homeless with his wife and two children. Again, Wedgwood offered to assist and ‘humanely gave him a little silver to relive his present necessities, for which he expressed his grateful thanks’. These actions gained Wedgwood an esteemed reputation, with a court report complimenting his ‘temperate language, his mild resolves and his becoming recommendations’.

Even after resigning from his magistrate position, Wedgwood still sought to help those in need. In 1840, he corresponded with social justice campaigner Caroline Norton (1808 – 77) regarding a case involving ‘poor little Margeret Walsh’. Walsh was arrested for begging, and Wedgwood had unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the magistrates to avoid the ‘odious stigma of imprisonment’. Despite the failure, Norton was ‘very grateful’ to Wedgwood.

Reviewing Wedgwood’s beliefs and principles, it is possible to understand why he attempted to save the lives of Pratt and Smith. He was clearly in two minds, a battle of conscience – his faith had conditioned him to view the pair’s acts as the definition of immorality, a crime so apparently devious no-one dared to name it. Yet, this belief was overridden by a strong sense of injustice, compassion and divine value attached to life. His conscience told to him to protest.

The unjustness and cruelty of Pratt and Smith’s case should be heard and commemorated as part of the long, continuing fight for equality, as well as the dangers of entrenched prejudice. Simultaneously, we should celebrate those who were willing to look past their own biases, take a risk, and support those who were punished because of sexual orientation.

Explore more of our Wedgwood Collection.

Find out more about the Progress Pride Flag.